Gibbs phenomenon

In mathematics, the Gibbs phenomenon, named after the American physicist J. Willard Gibbs, is the peculiar manner in which the Fourier series of a piecewise continuously differentiable periodic function behaves at a jump discontinuity: the nth partial sum of the Fourier series has large oscillations near the jump, which might increase the maximum of the partial sum above that of the function itself. The overshoot does not die out as the frequency increases, but approaches a finite limit.[1]

These are one cause of ringing artifacts in signal processing.

Contents |

Description

The Gibbs phenomenon involves both the fact that Fourier sums overshoot at a jump discontinuity, and that this overshoot does not die out as the frequency increases.

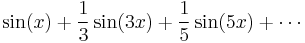

The three pictures on the right demonstrate the phenomenon for a square wave whose Fourier expansion is

More precisely, this is the function f which equals  between

between  and

and  and

and  between

between  and

and  for every integer n; thus this square wave has a jump discontinuity of height

for every integer n; thus this square wave has a jump discontinuity of height  at every integer multiple of

at every integer multiple of  .

.

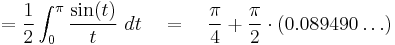

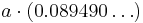

As can be seen, as the number of terms rises, the error of the approximation is reduced in width and energy, but converges to a fixed height. A calculation for the square wave (see Zygmund, chap. 8.5., or the computations at the end of this article) gives an explicit formula for the limit of the height of the error. It turns out that the Fourier series exceeds the height  of the square wave by

of the square wave by

or about 9 percent. More generally, at any jump point of a piecewise continuously differentiable function with a jump of a, the nth partial Fourier series will (for n very large) overshoot this jump by approximately  at one end and undershoot it by the same amount at the other end; thus the "jump" in the partial Fourier series will be about 18% larger than the jump in the original function. At the location of the discontinuity itself, the partial Fourier series will converge to the midpoint of the jump (regardless of what the actual value of the original function is at this point). The quantity

at one end and undershoot it by the same amount at the other end; thus the "jump" in the partial Fourier series will be about 18% larger than the jump in the original function. At the location of the discontinuity itself, the partial Fourier series will converge to the midpoint of the jump (regardless of what the actual value of the original function is at this point). The quantity

is sometimes known as the Wilbraham–Gibbs constant.

History

The Gibbs phenomenon was first noticed and analyzed by the obscure Henry Wilbraham.[2] He published a paper on it in 1848 that went unnoticed by the mathematical world. It was not until Albert Michelson observed the phenomenon via a mechanical graphing machine that interest arose. Michelson developed a device in 1898 that could compute and re-synthesize the Fourier series. When the Fourier coefficients for a square wave were input to the machine, the graph would oscillate at the discontinuities. This would continue to occur even as the number of Fourier coefficients increased.

Because it was a physical device subject to manufacturing flaws, Michelson was convinced that the overshoot was caused by errors in the machine. In 1898 J. Willard Gibbs published a paper on Fourier series in which he discussed the example of what today would be called a sawtooth wave, and described the graph obtained as a limit of the graphs of the partial sums of the Fourier series. Interestingly in this paper he failed to notice the phenomenon that bears his name, and the limit he described was incorrect. In 1899 he published a correction to his paper in which he describes the phenomenon and points out the important distinction between the limit of the graphs and the graph of the function that is the limit of the partial sums of the Fourier series (Nature: April 27, 1899, p.606). Maxime Bôcher gave a detailed mathematical analysis of the phenomenon in 1906 and named it the Gibbs phenomenon.

Explanation

Informally, it reflects the difficulty inherent in approximating a discontinuous function by a finite series of continuous sine and cosine waves. It is important to put emphasis on the word finite because even though every partial sum of the Fourier series overshoots the function it is approximating, the limit of the partial sums does not. The value of x where the maximum overshoot is achieved moves closer and closer to the discontinuity as the number of terms summed increases so, again informally, once the overshoot has passed by a particular x, convergence at the value of x is possible.

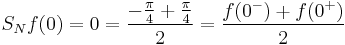

There is no contradiction in the overshoot converging to a non-zero amount, but the limit of the partial sums having no overshoot, because where that overshoot happens moves. We have pointwise convergence, but not uniform convergence. For a piecewise C1 function the Fourier series converges to the function at every point except at the jump discontinuities. At the jump discontinuities themselves the limit will converge to the average of the values of the function on either side of the jump. This is a consequence of the Dirichlet theorem.[3]

The Gibbs phenomenon is also closely related to the principle that the decay of the Fourier coefficients of a function at infinity is controlled by the smoothness of that function; very smooth functions will have very rapidly decaying Fourier coefficients (resulting in the rapid convergence of the Fourier series), whereas discontinuous functions will have very slowly decaying Fourier coefficients (causing the Fourier series to converge very slowly). Note for instance that the Fourier coefficients 1, −1/3, 1/5, ... of the discontinuous square wave described above decay only as fast as the harmonic series, which is not absolutely convergent; indeed, the above Fourier series turns out to be only conditionally convergent for almost every value of x. This provides a partial explanation of the Gibbs phenomenon, since Fourier series with absolutely convergent Fourier coefficients would be uniformly convergent by the Weierstrass M-test and would thus be unable to exhibit the above oscillatory behavior. By the same token, it is impossible for a discontinuous function to have absolutely convergent Fourier coefficients, since the function would thus be the uniform limit of continuous functions and therefore be continuous, a contradiction. See more about absolute convergence of Fourier series.

Solutions

In practice, the difficulties associated with the Gibbs phenomenon can be ameliorated by using a smoother method of Fourier series summation, such as Fejér summation or Riesz summation, or by using sigma-approximation. Using a wavelet transform with Haar basis functions, the Gibbs phenomenon does not occur.

Formal mathematical description of the phenomenon

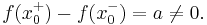

Let  be a piecewise continuously differentiable function which is periodic with some period

be a piecewise continuously differentiable function which is periodic with some period  . Suppose that at some point

. Suppose that at some point  , the left limit

, the left limit  and right limit

and right limit  of the function

of the function  differ by a non-zero gap

differ by a non-zero gap  :

:

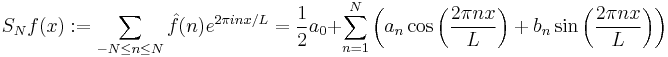

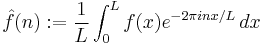

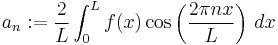

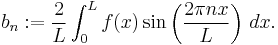

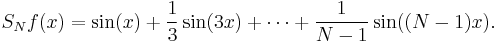

For each positive integer N ≥ 1, let SN f be the Nth partial Fourier series

where the Fourier coefficients  are given by the usual formulae

are given by the usual formulae

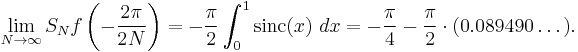

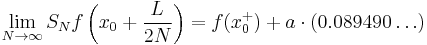

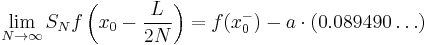

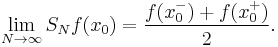

Then we have

and

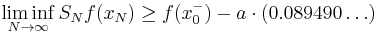

but

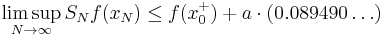

More generally, if  is any sequence of real numbers which converges to

is any sequence of real numbers which converges to  as

as  , and if the gap a is positive then

, and if the gap a is positive then

and

If instead the gap a is negative, one needs to interchange limit superior with limit inferior, and also interchange the ≤ and ≥ signs, in the above two inequalities.

Signal processing explanation

From the point of view of signal processing, the Gibbs phenomenon is the step response of a low-pass filter, and the oscillations are called ringing or ringing artifacts. Truncating the Fourier transform of a signal on the real line, or the Fourier series of a periodic signal (equivalently, a signal on the circle) corresponds to filtering out the higher frequencies by an ideal (brick-wall) low-pass/high-cut filter. This can be represented as convolution of the original signal with the impulse response of the filter (also known as the kernel), which is the sinc function. Thus the Gibbs phenomenon can be seen as the result of convolving a Heaviside step function (if periodicity is not required) or a square wave (if periodic) with a sinc function: the oscillations in the sinc function cause the ripples in the output.

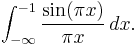

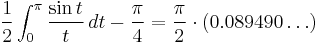

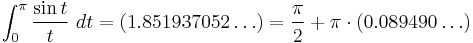

In the case of convolving with a Heaviside step function, the resulting function is exactly the integral of the sinc function, the sine integral; for a square wave the description is not as simply stated. For the step function, the magnitude of the undershoot is thus exactly the integral of the (left) tail, integrating to the first negative zero: for the normalized sinc of unit sampling period, this is  The overshoot is accordingly of the same magnitude: the integral of the right tail, or, which amounts to the same thing, the difference between the integral from negative infinity to the first positive zero, minus 1 (the non-overshooting value).

The overshoot is accordingly of the same magnitude: the integral of the right tail, or, which amounts to the same thing, the difference between the integral from negative infinity to the first positive zero, minus 1 (the non-overshooting value).

The overshoot and undershoot can be understood thus: kernels are generally normalized to have integral 1, so they result in a mapping of constant functions to constant functions – otherwise they have gain. The value of a convolution at a point is a linear combination of the input signal, with coefficients (weights) the values of the kernel. If a kernel is non-negative, such as for a Gaussian kernel, then the value of the filtered signal will be a convex combination of the input values (the coefficients (the kernel) integrate to 1, and are non-negative), and will thus fall between the minimum and maximum of the input signal – it will not undershoot or overshoot. If, on the other hand, the kernel assumes negative values, such as the sinc function, then the value of the filtered signal will instead be an affine combination of the input values, and may fall outside of the minimum and maximum of the input signal, resulting in undershoot and overshoot, as in the Gibbs phenomenon.

Taking a longer expansion – cutting at a higher frequency – corresponds in the frequency domain to widening the brick-wall, which in the time domain corresponds to narrowing the sinc function and increasing its height by the same factor, leaving the integrals between corresponding points unchanged. This is a general feature of the Fourier transform: widening in one domain corresponds to narrowing and increasing height in the other. This results in the oscillations in sinc being narrower and taller and, in the filtered function (after convolution), yields oscillations that are narrower and thus have less area, but does not reduce the magnitude: cutting off at any finite frequency results in a sinc function, however narrow, with the same tail integrals. This explains the persistence of the overshoot and undershoot.

Thus the features of the Gibbs phenomenon are interpreted as follows:

- the undershoot is due to the impulse response having a negative tail integral, which is possible because the function takes negative values;

- the overshoot offsets this, by symmetry (the overall integral does not change under filtering);

- the persistence of the oscillations is because increasing the cutoff narrows the impulse response, but does not reduce its integral – the oscillations thus move towards the discontinuity, but do not decrease in magnitude.

The square wave example

We now illustrate the above Gibbs phenomenon in the case of the square wave described earlier. In this case the period L is  , the discontinuity

, the discontinuity  is at zero, and the jump a is equal to

is at zero, and the jump a is equal to  . For simplicity let us just deal with the case when N is even (the case of odd N is very similar). Then we have

. For simplicity let us just deal with the case when N is even (the case of odd N is very similar). Then we have

Substituting  , we obtain

, we obtain

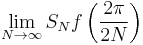

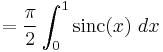

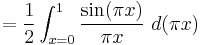

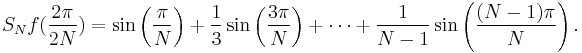

as claimed above. Next, we compute

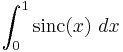

If we introduce the normalized sinc function,  , we can rewrite this as

, we can rewrite this as

But the expression in square brackets is a numerical integration approximation to the integral  (more precisely, it is a midpoint rule approximation with spacing

(more precisely, it is a midpoint rule approximation with spacing  ). Since the sinc function is continuous, this approximation converges to the actual integral as

). Since the sinc function is continuous, this approximation converges to the actual integral as  . Thus we have

. Thus we have

which was what was claimed in the previous section. A similar computation shows

Consequences

In signal processing, the Gibbs phenomenon is undesirable because it causes artifacts, namely clipping from the overshoot and undershoot, and ringing artifacts from the oscillations. In the case of low-pass filtering, these can be reduced or eliminated by using different low-pass filters.

In MRI, the Gibbs phenomenon causes artifacts in the presence of adjacent regions of markedly differing signal intensity. This is most commonly encountered in spinal MR imaging, where the Gibbs phenomenon may simulate the appearance of syringomyelia.

See also

- Compare with Runge's phenomenon for polynomial approximations

- Sigma approximation

- Sine integral

- Henry Wilbraham

Notes

- ^ H. S. Carslaw (1930). Introduction to the theory of Fourier's series and integrals (Third Edition ed.). New York: Dover Publications Inc.. Chapter IX. http://books.google.com/books?id=JNVAAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=intitle:Introduction+intitle:to+intitle:the+intitle:theory+intitle:of+intitle:Fourier%27s+intitle:series+intitle:and+intitle:integrals+inauthor:carslaw#PPA264,M1.

- ^ Hewitt, Edwin; Hewitt, Robert E. (1979). "The Gibbs-Wilbraham phenomenon: An episode in fourier analysis". Archive for History of Exact Sciences 21 (2): 129–160. doi:10.1007/BF00330404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00330404. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ M. Pinsky (2002). Introduction to Fourier Analysis and Wavelets. United states of America: Brooks/Cole. p. 27.

References

- Gibbs, J. W., "Fourier's Series". Nature 59, 200 (1898) and 606 (1899).

- Antoni Zygmund, Trigonometrical series, Dover publications, 1955.

- Wilbraham, H. On a certain periodic function, Cambridge and Dublin Math. J., 3 (1848), pp. 198–201.

- Paul J. Nahin, Dr. Euler's Fabulous Formula, Princeton University Press, 2006. Ch. 4, Sect. 4.

External links and references

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Gibbs Phenomenon". From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource.

- Prandoni, Paolo, "Gibbs Phenomenon".

- Radaelli-Sanchez, Ricardo, and Richard Baraniuk, "Gibbs Phenomenon". The Connexions Project. (Creative Commons Attribution License)

- Horatio S Carslaw : Introduction to the theory of Fourier's series and integrals.pdf (introductiontot00unkngoog.pdf ) at archive.org

![S_N f\left(\frac{2\pi}{2N}\right) = \frac{\pi}{2} \left[ \frac{2}{N} \operatorname{sinc}\left(\frac{1}{N}\right) %2B \frac{2}{N} \operatorname{sinc}\left(\frac{3}{N}\right)

%2B \cdots %2B \frac{2}{N} \operatorname{sinc}\left( \frac{(N-1)}{N} \right) \right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/313212d28121c036c15ee92f353aae66.png)